Diane von Furstenberg has never forgotten what a well-known male designer once told her: “Women make clothes. Men make costume.”

It was a dictum that has stuck with her for years, and one that she personally believes has some merit. After all, she says in her delicious Belgian drawl, “Madeleine Vionnet invented the bias cut. And what does bias do? It creates stretch in a woven fabric. Women understand the movement of the body; women understand body language in terms of function. At the end, fashion is not art, it’s design. And design is about functionality.”

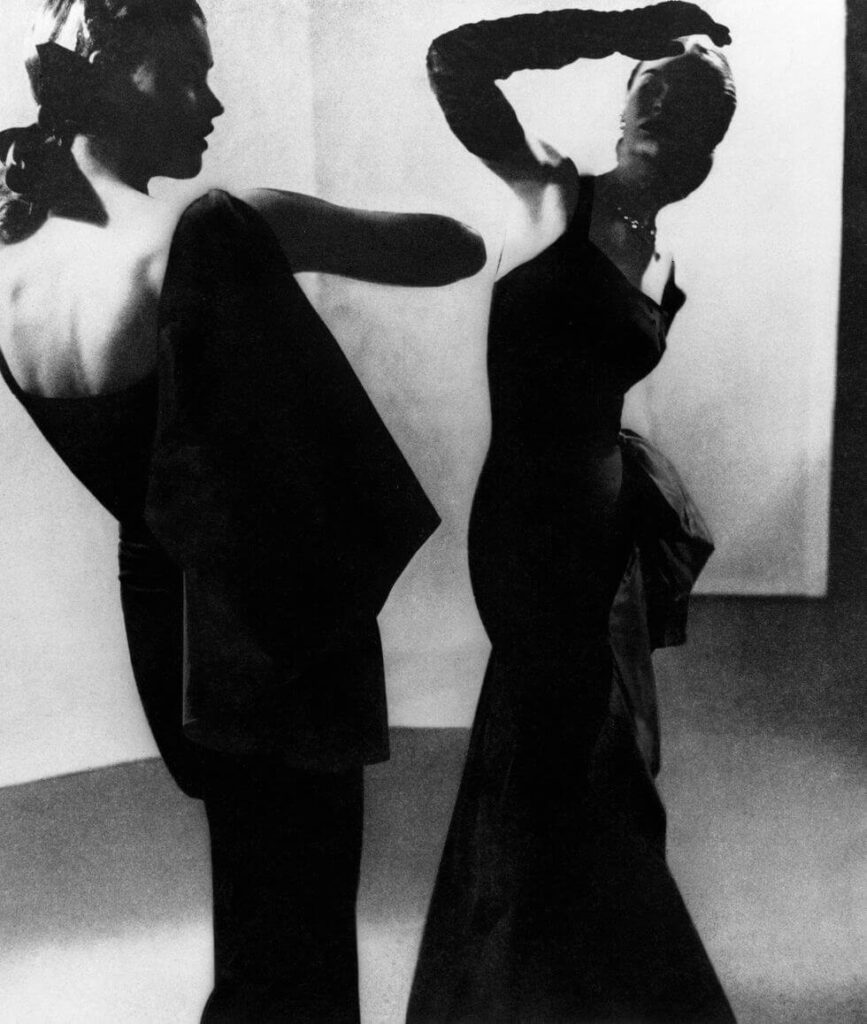

A Madame Grès design, 1946.

It’s certainly true that several prominent female-led labels have helped push fashion in a more practical, comfort-oriented direction: In addition to Vionnet’s bias cut, there are the flowing pants popularized by Coco Chanel, the sportswear of Claire McCardell, and the proto-athleisure of Norma Kamali. But alongside them have been women who’ve created elaborate, delightfully impractical fashion-as-art, from Rei Kawakubo to Iris van Herpen.

So female designers are certainly not monolithic in their approach. But they do have one thing in common: They continue to be underrepresented at the highest echelons of the industry. In honor of International Women’s Day and Women’s History Month, ELLE interviewed designers at the helms of brands about their touchstones, how their gender identity informs their work (if it does), and what fashion can do to correct the imbalance.

Jeanne Lanvin at work in the 1930s.

But back to that opening declaration: For some of those I spoke to, it has an element of truth. “Women designers think differently; they are intuitive and incredible problem-solvers,” says Tory Burch. “There is a realness to what I do, but never at the expense of creativity.” That doesn’t mean she’s simply dressing versions of herself—that approach applies “even if I won’t personally wear it. Designing only for myself would not be interesting.” For Silvia Venturini Fendi, artistic director of accessories, menswear, and children at Fendi, “Everything I have done speaks about me and my experiences, and therefore about my being a woman.” And being a woman designing men’s collections “has surely contributed to bringing a more open vision to it by breaking down strictly male codes.” Dior creative director Maria Grazia Chiuri professes a fascination with the idea of “fashioning one’s identity” through clothing. “What is most important, I believe, is the relationship we establish with clothes as women,” she says. “The fact that they serve a decorative purpose, that they speak of adornment but can simultaneously be actual tools of affirmation and empowerment.”

Rei Kawakubo.

Gabriela Hearst often finds herself saying that “I don’t think I could be a designer if I wasn’t a woman. I always joke, but it’s true: I understand water retention, and how our bodies change monthly, and how our bodies change through our decades. And I also understand what parts of the body all women are happy to show, and what parts are a bit more sensitive.” Her goal in designing for women overall, she says, is to “frame them more than encage them.”

Batsheva Hay, known for her outré prairie dresses and collaborations with brands like Laura Ashley, is in the “designing for herself” camp, saying that if she didn’t like a piece, “I cannot imagine that my customer would either,” while Oscar de la Renta co–creative director Laura Kim asks rhetorically, “If I would not want to wear one of my own designs, who would?”

Vivienne Westwood spring 1984.

For some designers, their experience living in a female body helps inform their work in other ways. Take Kawakubo, who, with her “Body Meets Dress, Dress Meets Body” collection for Comme des Garçons, presented an avant-garde take on the female form that was simultaneously hilarious and uncanny. Or Simone Rocha, who unveiled a collection for spring 2022 inspired by nursing bras and swaddling clothes—territory we’ve rarely seen male designers tackle. “My designs come from a personal place, and I’m personally invested in every one,” Rocha tells me. “So that is what really informs my work, but of course naturally being a woman designing for women is a part of that.”

After the overturn of Roe v. Wade and post-#MeToo, this conversation feels even more urgent. When Mellissa Huber and her cocurator Karen Van Godtsenhoven were first planning their Costume Institute exhibit Women Dressing Women in 2019, the world was in a very different place. The original impetus for the show was the 100th anniversary of women’s suffrage in the United States. The now-opened exhibit, which runs through March 10th, includes pieces from Vionnet, Schiaparelli, and many of the designers featured here, but it also spotlights lesser-known names from the past like Georgina Godley and Ann Lowe. A question Huber, the Institute’s associate curator, has been getting a lot is whether she sees a difference in the way women and men approach design. “I personally don’t believe that gender informs one’s approach to design per se,” she says, “but I think lived experience does. Every designer has their own educational background, their own training, their own personal attributes like their nationality, age, race, and ability.”

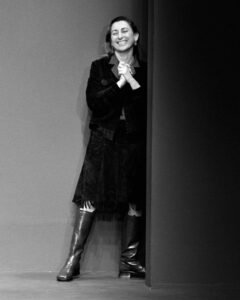

Miuccia Prada taking her bow at Prada’s fall 1999 runway show.

One of the surprising aspects of the exhibit is seeing how during the interwar period, there were far more female designers heading brands than there are today, a number that started to go down after World War II. But even in this seemingly golden era, there were limits. Huber explains that “even in the early 20th century, when we had so many women who were leading design houses—if you look at the notes from the Chambre Syndicale de la Haute Couture, the governing body of fashion in France, many of them would have their male business managers or lawyers attend meetings to represent the house.”

That unwillingness to invest in female-led businesses persists today, amid so many male-dominated VC funds and C-suites. As Hearst says, “There’s a subconscious bias if you’re a male executive of a certain age group, and you’ve worked and lived in certain cities and places, and you have a certain education, saw certain ads, and were fed certain propaganda. You may feel more comfortable talking business with a male face in front of you than a female face in front of you.” (“That’s an unproven theory by me,” she adds, but anecdotes I’ve heard from multiple female founders seem to back it up.)

In this environment, what can the fashion industry do to nurture, promote, and support female talent? For Aurora James, designer of Brother Vellies, the answer is replicating the support structures she had coming up. “I was given a chance by brilliant women in fashion who recognized my talent and took their time and financial resources to support me. It’s critical we continue with that legacy,” she says. It’s something she’s doing with her nonprofit, Fifteen Percent Pledge, which aims to support Black-owned businesses and gave out $305,000 in grants in 2023. “But there is still so much to do,” James says. “I think as consumers, we also have to be cognizant of our own spending. Is 50 percent of our fashion spend going to women?”

For Hearst, who has collaborated with female artisan groups including Manos del Uruguay and the quilters of Gee’s Bend, the goal is pulling other women up with her. “If you empower women, you empower community.…We need female leadership in all areas of our life, because we tend to want to uplift others.” And what’s more, she says, “We won’t be able to resolve the issues that we are facing as a species if women are not in leadership positions.” Chiuri has undertaken a similar project with the Chanakya School of Craft in Mumbai, where female artisans are trained in embroidery while also embarking on more traditional courses of study.

Collina Strada spring 2024.

Johanna Ortiz, who is based in her home city of Cali, Colombia, would also like to see more resources going to women located outside the four fashion capitals of New York, London, Milan, and Paris. “Incredible designs and fashion emerge from all corners of the world,” she says. “It would be wonderful to witness more representation, programming, and opportunities for designers and brands outside these networks, lacking the extensive resources available in those hubs. There is an abundance of talent waiting to be discovered.”

Several of the designers we polled mentioned the importance of supporting working parents. “Working in fashion can be all-consuming, and in many cases, working mothers are not set up to thrive,” says Burch, who has focused on flexibility at her own company so that “women [don’t] have to choose between having a career and having a fulfilling life.” Adds Venturini Fendi: “Nursery schools at work are essential, especially in countries where childcare is still delegated to mothers only.”

Simone Rocha spring 2024.

For all the complexities of the issue, when it comes to fostering female talent, the answers can be devastatingly simple. Says Maria Cornejo: “You can wear them and promote them.” Collina Strada founder and creative director Hillary Taymour echoes, “Start hiring them as creative directors.” And Catherine Holstein of Khaite says, “Instead of the narrative that there is a lack of female creative directors, the industry can do more to prop up the many talents that do exist and are here, still standing. Still working.”

Véronique Hyland, in her article “What Do Women Designers Want?” explores the unique perspectives and aspirations of female designers, highlighting how their experiences and visions are reshaping the fashion industry.

To gain insights into the motivations of these designers, you can read Véronique Hyland’s full article on ELLE.